Emerging Metropolis: Interview with Daniel Soyer

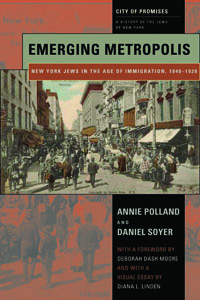

Emerging Metropolis: New York Jews in the Age of Immigration, 1840-1920 (NYU Press, 2012) is the second volume of City of Promises: A History of the Jews of New York, a three-volume series that is, surprisingly enough, the first ever comprehensive history of New York Jews. The series, overseen by scholar Deborah Dash Moore, tells the story of the largest Jewish community in Jewish history.

In Emerging Metropolis, co-authors Annie Polland, Vice-President of Programs and Education at the Lower East Side Tenement Museum, and Daniel Soyer, Professor of History at Fordham University, draw on original research to explore the encounter of Central European and East European Jews with New York City and describe New York’s transformation into a “Jewish city.”

Yedies editor Roberta Newman interviewed Daniel Soyer.

RN: What makes the time period of your particular volume in this series (1840 to 1920) unique in the history of Jews in New York?

DS: This period is really when New York went from being a small settlement on the edge of the Jewish world to being the greatest Jewish metropolis of all time. In 1840, there were 7,000 Jews in New York. That was already quite an increase from twenty years before, but still a relatively small community. By 1920, there were over a million and a half Jews in New York City, and this was fueled by an almost century-long wave of immigration, mainly from Central Europe first, and then Eastern Europe. That’s what makes this period unique in terms of where it fits in, let’s say, with the entire history of the Jews of New York, which the three-volume set City of Promises covers.

What makes our book a little different from previous books, like World of Our Fathers by Irving Howe and The Promised City by Moses Rischin, is that we include this entire wave of immigration, which most people consider two separate waves, and The Promised City and World of Our Fathers really only deal with the second half of this period. Those are great books, but that’s one way in which our book differs.

RN: Traditionally, we think of that time period as covering several different waves of Jewish immigration, but you’re saying it was actually one wave?

DS: Within the book we do have separate chapters which deal with the earlier wave, or the earlier sub-wave and the later sub-wave, but the entire book in a sense treats them as one period. And we also try to break down the dichotomy between what many people nowadays know as the German Jews and the people who are known as the Eastern European Jews.

First of all, when the Central Europeans arrived, many of them weren’t really that German. They were from places like Posen, which was western Poland, that was under the control of Prussia, and therefore, officially, they were coming from a German state. But really, they were Polish Jews. Other people were coming from other peripheries of the German cultural territory in Central Europe. And many of these people were actually Yiddish-speaking, although their official communal language was often German, and there wasn’t that much Yiddish organizational or cultural life at the time. People spoke Yiddish on the street and in their homes. So they were only thinly Germanized—not as German as some people make out. It’s important to remember that most of these people were poor immigrants, and they had a period of adjustment, and it took some time before they rose socially and integrated into American culture, just like the Eastern Europeans did later.

So we’re not the first people to notice this, but we do try to emphasize that the two parts of this big century-long wave resembled each other in their origins in some ways.

RN: One of the other things that is particularly ambitious about this book is that it’s a political, cultural, economic, and social history all rolled into one. Did writing about all those different historical perspectives pose any special challenges?

DS: Yes, we had to cover a tremendous amount of ground. It’s a fairly long time period, and by the end this is a community of one and a half million people which is composed of German-speakers, Yiddish-speakers, and maybe by then in the majority, English-speakers. Of course there were also Ladino-speakers and smaller groups of Russian- and Hungarian-speakers, and they contributed to all of these communities and the cultures in all of these languages. They had a huge array of political opinions. By the end of the period, too, there was a massive number of working-class Jews; and there was a thin, fantastically wealthy elite. So it was a very, very complex community. It was a challenge to try to be comprehensive and still be able to a) tell a story, and b) frankly, fit within the page limits that we had from the publisher, while showing how all of these different facets of the community fit together as well as had their separate existences.

RN: Were there any surprises for you in researching this book?

DS: One surprise that Annie Polland uncovered is the extent of the Jewish presence in mid-nineteenth-century Five Points. People know about the infamous neighborhood of Five Points in Lower Manhattan, which was one of the most notorious slums in the world in the mid-nineteenth century. It’s usually thought of as an Irish immigrant neighborhood but really there were many different kinds of people living there, and there was even a Jewish presence: a minority, but nevertheless a substantial Jewish presence. There was quite an active community there. The way we found this is through the records of the Association for the Free Distribution of Matsot to the Poor, which are at the American Jewish Historical Society. And they have distribution lists, so you could actually map out where the recipients were and where the donors were. Many of the recipients—poor immigrant Jews of the mid-nineteenth century—were in Five Points.

One of the collections at YIVO that we used the most was the Immigrant Autobiographies Collection [RG 102 American-Jewish autobiographies]. This was a collection that I had worked with before, and was therefore familiar with. And it just has great details of people talking about their lives and talking about what their apartments and first jobs were like, and about their encounters with landsleit in the landsmanshaftn and on the streets, how they went to lectures—all kinds of things. We also used the records of the Educational Alliance, which as you know are very detailed and very extensive, as well as the Yiddish press, which is available in the YIVO Library. We couldn’t have done it without YIVO.

RN: Did these Jewish immigrants physically change the face of New York City?

DS: Absolutely. One of the things that we tried to do a little bit is to use places and buildings as indicators of social and political and economic processes that were going on. Certainly by the end of the nineteenth century Jews are beginning to build grand synagogues, but beyond that, also leaving their marks on things like the Forward building, the Jarmulowsky Bank building, institutional buildings all over the city both religious and secular. And of course even in this time period as commercial builders. Many of the tenements, not only in the Lower East Side but also in upper Manhattan, East Harlem, the Bronx, Brooklyn, were built by immigrant Jewish builders, so entire neighborhoods—Brownsville, for example—were created by Jewish builders and by the first wave of tenants in the buildings they built.

RN: Aside from that, do you think that the Jews of 1840 to 1920 have a legacy in New York City today?

DS: I think it’s impossible to talk about New York City as the cultural capital of America without talking about the Jewish influence. Of course there were others before them, and at the same time as the Jews were active there were the Irish and African Americans, but the importance of Jews not only as producers but as an audience for high culture, such as the Metropolitan Opera or Broadway theater, is I think unmatched. Even Hollywood really began as a colony of Jewish New York. The film industry really began in New York. A number of Jews, particularly immigrant Jews, got involved in this new industry from which they were not excluded because there hadn’t been an industry before, and started to build it, and they took it out west where it continues today, but it was really a colony of Jewish New York.

And then there’s the New York language, of course, with all its Yiddishisms. And New York politics with its century of concern for social justice and what some historians have called a kind of social democracy in one city, was in great part—again, not exclusively—a creation of a special kind of Jewish social democratic politics. So I think there are a lot of ways in which Jews have left a lasting impression on the city. One that continues to change, of course, and some of these things fade, and new things come about in new eras. The number of Jews has fallen in New York, although in the last ten years for the first time in half a century it’s starting to rise again, but of course it’s now increasingly Orthodox and Hasidic in character, and this will be a different kind of Jewry which will have a different kind of influence on the city in the future.

RN: We talk of New York becoming a Jewish city at that time, but isn’t it true that at no point have Jews ever actually been the majority of residents?

DS: That was actually another aim of the book, was to write a history of the Jews in New York City, making it perfectly clear that although there was this huge Jewish metropolis within the city, they were never a majority. And in fact, although they were the largest ethnic group by 1920, they were not the largest religious group because the Catholics were a much larger group. One of the goals of the book was to show the connections between Jews and the city as a whole.

Interview transcribed by Alix Brandwein, and edited for length and clarity.

Read an excerpt from the book.

Buy the book.