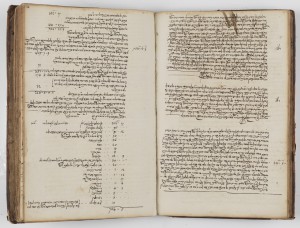

On Sunday, October 6, 2013, YIVO and the Center for Jewish History will host a one-day conference, Hidden from History: The Pinkas of the Metz Rabbinic Court, 1771-1789, in conjunction with an exhibition and two other public programs celebrating the pinkas (register) of the bet din (rabbinic court) of the Jewish community of Metz, France, two leather-bound volumes preserved in the YIVO Archives. Brimming with details of commercial transactions involving Jews and non-Jews, family law, inheritance, modes of jurisprudence, and recourse to civil courts, the Pinkas is a monument to an extraordinary community and its remarkable rabbinical court.

- Visit the exhibition and symposium web site and buy tickets to the events.

- Attend the conference on October 6.

- Attend the lecture by Rabbi Moshe Arye Bamberger (Head of the Bet Din of the Metz Jewish Community, France) on October 7.

Jay Berkovitz

Jay BerkovitzProfessor Jay Berkovitz of the University of Massachusetts is the author of the upcoming book, Protocols of Justice: The Pinkas of the Metz Rabbinic Court 1771-1789 (Brill), a transcription and annotated translation of the 400,000-word document.

On September 9, he sat down with Yedies Editor Roberta Newman to talk about the pinkas. This interview is the first in a three-part series.

RN: How rare a document is this in terms of French Jewish life? Are there other pinkasim out there?

JB: There are other pinkasim. The word pinkas means register and it refers not only to a court register but also to communal registers that include such things as communal bylaws and registers of wills and of expenditures of charitable organizations. As a register of court proceedings, it is actually quite rare. There is another one from the Alsatian town of Niedernai. There are, of course, pinkasim of this sort in other places such as Frankfurt. The Frankfurt pinkas, the court diary of the court scribe, has recently been published by Edward Fram of Ben Gurion University in a very fine book called A Window on Their World. We have here and there other pinkasim that have never before been published. That's the rule. But there aren't many that are extant.

This pinkas of Metz, in all likelihood, is the most complete, the most developed, probably the most detailed of all the pinkasim of this genre that we have today, and as a result, can tell us a story that none of the other pinkasim can tell. Because of the nature of court records and all the details that accompany the sort of litigation that occurs several times a week in the court, we now have an extraordinary amount of information concerning the culture of the Jewish community. It includes inventory lists and descriptions of settlements involving widows, or divorce settlements of estates belonging to orphans. And that information tells us so much about the acculturation of Jews in Metz, their exposure to the finer elements of French life and culture – especially material culture. We can also see their familiarity with legal procedures, with the administrative, bureaucratic processes, a knowledge that was expected of all residents of Metz, not only Jews. Jews, in many ways, find themselves living a life that is extraordinarily similar to the life lived by non-Jewish Frenchmen at that time. Here they are, a community living in its own area in Metz, with certain legal limitations that have been imposed on them, and at the same time, they're living a life that is extraordinarily similar to that of their Christian neighbors.

This is a story that we could never have told before. It's a story that is only partially told in the Pinkas Hekehillot, the communal pinkas that is the property of JTS Archives Rare Book Room. This is probably a document that should be read in tandem with that one.

RN: Do you think that the records of rabbinical courts are a neglected resource in Jewish scholarship?

JB: They're definitely neglected and there aren't so many of them. One of the reasons they're neglected is, first of all, they're difficult to understand. One has to have technical training in Jewish law. One has to become expert in paleography because these are manuscripts and not always easy to read. But with time, one can learn how to read them. Often, the language is terse and in some ways elusive; it doesn't always provide a full description of what it is at stake, legally or otherwise.

Part of the difficulty is that the pinkas is over 400,000 words. That's an enormous amount of material. Making sure that the transliterated text is accurate took a great deal of time. But what I'm hoping that the publication of the pinkas with my annotations and essay will excite Jewish historians with the prospect of using the pinkas of Metz and other pinkasim in order to generate a richer understanding of Jewish life, not necessarily from the top down but also from the bottom up. The pinkas, as much as it represents the view of the judges, also describes very clearly the consumers of the law. As a document, it displays very clearly the responsiveness of the court to the changes that were going on within the community.

RN: This document only represents about 18 years of the court. Have we lost the record of what came before that? Or was there less meticulous record-keeping previously?

JB: I believe that the court records were kept prior to 1771, but they were never systematically preserved. There's no doubt that records were kept and that casual litigants were given copies because that's the way it was done. Something happened in the early 1770s and it happened not only in France, but also in Germany and other places to the east of Frankfurt that seemed to have resulted in a desire either by communities or by governments to have Jewish communities record their court cases in registers that would be preserved as they had not been before. Exactly why, we cannot say for sure. I think part of it has to do with the increasing traffic between the Jewish court and the French civil courts. These court records of the bet din provide something of a record of the litigation that's going on in the non-Jewish courts as well as in the Jewish courts, very often complicated cases involving non-Jews. For example, partnerships involving Jews and non-Jews -- some element of a partnership that's gone sour and is an issue that requires litigation in the French civil courts. Ultimately the rulings of the rabbinic court in Metz are going to depend on the findings of that civil court. And in such an instance, there needs to be some record of that legal action. So, it may well be that with the increased activity of Jewish litigation in non-Jewish courts, there was a reason why a stronger record of this would be desired by the Jewish community.

It's never really stated at any specific point why the document was written or for whom it was intended. Nevertheless, we can learn from the way it was put together that it was very much a document that reflects communal values and not only the values of the elite. So often we find the bet din exploring its legal relationship with the kahal, the executive leadership of the community. The Metz Jewish community has an active legislation. The job of the bet din is to judge according to that legislation. Sometimes that legislation is inconsistent with Jewish law -- communal law is not always identical to Jewish law. The bet din, because it is an agency of the community, is obligated to interpret the law in accordance with the communal understanding.

RN: What particular assumptions about the lives of Jews in France and about modern Jewish history in general did the contents of the pinkas challenge for you? What was the biggest surprise?

JB: I think, first and foremost, there is the issue of insularity. It has been pretty much an axiom that Jews in traditional society prior to the French Revolution, and especially in northeastern France, lived apart from French culture. Supposedly, it wasn't until the French Revolution that they became exposed to the broader forces and currents of French life. And the nineteenth century, of course, is indeed an era of much greater integration, assimilation, and the like. In fact, as late as 1788, the Jews are described in one journal, called the Almanac and published in Metz, as "un peuple isolée,”an isolated people. And why exactly they were described that way is something else, but the point is that this is the general assumption in the historiography. What I've found is that this community in Metz was far from being insular. It was very much exposed to the broader developments in French life, culture, economy, and law.

In particular, I found that the role of women in the Jewish community in Metz appears to be perhaps more advanced than we would have thought and that there was something that resembles some of the more progressive developments in the status of women in French society in the latter part of the seventeenth century.

I have discovered within this document, really, the makings of an entirely new understanding of how Jews lived in relationship to non-Jews and general society. I’ve also been confirmed in my understanding of the adaptability of Jewish law to modern life.

Interview edited for length and clarity.