Two Worlds/Tsvey Veltn: Interview with Benjy Fox-Rosen

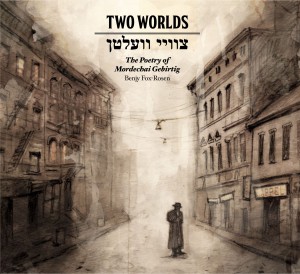

On January 15, 2014, at 7 pm, Yiddish musicianBenjy Fox-Rosen will release Two Worlds/ Tsvey Veltn (Golden Horn Records),a new song cycle based on the poetry of master Yiddish and Polish writer Mordechai Gebirtig (1877-1942) at a concert at YIVO, co-presented with the American Society for Jewish Music and the Center for Traditional Music and Dance.

On January 15, 2014, at 7 pm, Yiddish musicianBenjy Fox-Rosen will release Two Worlds/ Tsvey Veltn (Golden Horn Records),a new song cycle based on the poetry of master Yiddish and Polish writer Mordechai Gebirtig (1877-1942) at a concert at YIVO, co-presented with the American Society for Jewish Music and the Center for Traditional Music and Dance.

He was recently interviewed by Leah Falk.

Attend the event.

LF: Tell me a little bit about how you got started with Yiddish folk music.

BFR: I got interested in Yiddish folk music in a couple of different ways at a couple of different times. One was when I was in high school: one of my parents’ friends was an amateur musician who would come over Saturday afternoons and play with my brother and me, a few klezmer tunes and a couple of Israeli folk tunes—I didn’t really continue with that. Then I came to New York to study jazz music and realized relatively quickly, “I’m not really going to be a jazz musician.” Then I joined a band in 2005 called Luminescent Orchestrii, which was playing different kinds of Balkan music and some klezmer music. I thought, I want to sing in this band, and then said, well, of course if I’m going to sing in an Eastern European language it should probably be Yiddish, or at least should be Yiddish first.

LF: Did that connect back to the music you experienced as a kid?

BFR: I didn’t really grow up around Yiddish language that much, but my grandmother, who was a Polish Jew from Krakow, she really likes this poet, Mordechai Gebirtig, so she introduced some of his poetry to me as a teenager. She’s always been a terrible singer, so she would try to sing us these songs, and it would be like, what are these, you’re not a good singer, we don’t understand the words. But then later I became interested in that body of work, and when I started looking at Yiddish songs to learn, the initial body of work I looked into was actually these poems by Mordechai Gebirtig, and some of the poems I wrote music for a couple years later [on Tsvey Veltn].

LF: My next question was going to be, “Why Gebirtig?” Some of his songs are on your first album [Tick, Tock], too.

BFR: [The songs on Tick Tock] are his songs [with my arrangements], not ones I wrote music for. [My] original compositions there were going to be some on that album but then I decided it would be best to make a record of just my own settings of his music and one of just arrangements of traditional music.

So I was introduced to him by my grandmother and once I became interested in Yiddish music more broadly, it was like, oh, Gebirtig, everybody sings his songs, and he has such a huge range of songs in terms of subject matter. He’s known for a lot of nostalgic songs, and those are the songs that are primarily sung and passed down, but you could completely ignore a portion of his work and say he was a real working-class hero writing anthems for working-class people. Or you could say, no, he was a sentimental religionist who wanted the children to grow up and be great scholars. He has such a huge body of work that you can really go in—and this is what I did, I guess—and take whatever you want to make whatever sort of narrative structure, whatever idea you want to broadcast about Gebirtig.

LF: On this album, you’re consciously making something new out of something old, but also something incomplete, because we don’t have his music to those poems. I’m interested in how you negotiate the line between honoring the text and writing a modern composition.

BFR: I think it has to do with a couple of different things: language, primarily, is important: staying with the internal rhythms and accents of Yiddish itself. I’ve been studying Yiddish for 7 years now, and speak it decently… but I asked for help when I needed help. People are generous with their time in this regard. I think honoring the rhythm of the language is one thing, and also, if I were to observe my own composition style in terms of setting Yiddish text, I would say that my compositions from a few years ago are more outside of the Yiddish music vocabulary; now, as I’m spending more time studying folk idiom, my new compositions are sounding a little more folksy, which I’m kind of annoyed about.

LF: Listening to the album, I hear a lot of jazz influence.

BFR: There’s a lot of improvised music and that’s my background, so I think doing settings in a really traditional way wouldn’t have fit, at least from my own perspective—wouldn’t have fit my own musical background and what’s happening in my ears outside of Yiddish music.

LF: You’re calling this album a song cycle, which has connotations that go with classical music or jazz—it suggests a longer narrative. You were talking before about arranging the songs to convey a narrative arc. Can you describe that?

BFR: Basically, there are twelve poems in the piece. I didn’t take all these poems and put them in order and say “this is what’s going to happen”—I had written about eight or so settings before saying, hey, I should make this into a song cycle. With that frame of the pieces that I had already composed the music for, I searched through some books , texts by Gebirtig that hadn’t been set to music, and I tried to find things that would complete a sort of abstract arc—I don’t know if it would have been possible to be too explicitly narrative.

The record starts from the perspective of a child. The first half of the pieces don’t have anything to do with war or the Holocaust, and then there’s one piece that is called “The Bells Ring” [Yiddish] and it sort of shifts—from there to the end all the poetry is related to the Holocaust or wartime. Or not all of them, but that’s where the narrative arc goes. The second-to-last piece is called “A Day of Revenge” and I set it to a very pop tune but the text is horrible—we should have revenge, it’ll be a great day when everybody else is finally suffering—like the coda at the end of the Book of Esther, which says something like “and the Jews went out and killed everybody and they had a great time.” Then there’s one more piece at the end called “Sunbeam,” and it’s about the possibilities of renewal and freedom, in a very uncynical, maybe even a naïve way. And that’s how the piece ends.

LF: Gebirtig wrote “A Day of Revenge” when he was in the Krakow Ghetto.

BFR: Both of the last two he wrote within six months of each other, maybe less. To focus on his poetry from 1941-1942, you see he’s so bitter and angry; but then some of the poems are unclear in themselves, what exactly he’s thinking.

These texts were published in 1949, in a Workmen’s Circle book reprinted with additional text. The 1920 book that Gebirtig published in Krakow, Mayne Lider, was reprinted in New York, and then in 1957 in Israel a very small press put out these poems that they found in archives in New York and in Jerusalem. The story is that Gebirtig gave a stack of poems to the daughter of his friend Julius Hoffman—Gebirtig couldn’t read or write music so Hoffman was his transcriber. Gebirtig gave this pile of poems to [Hoffman’s] daughter when she was leaving Krakow and she took them with her and they ended up sort of scattered in different places. That book was published in 1997, just in Yiddish. I did try, at the urging of the record company, to try to get in touch with the press to make sure there were no permissions problems—and they don’t exist. The editor died years ago, they published four books in the ‘90s and they don’t exist anymore.

LF: So nobody’s going to sue you.

BFR: I don’t think anybody’s going to sue me. But it wouldn’t have been possible without that scholarship, being able to open up a book and say, oh, here are 70 poems.

LF: Is this project is the end of your engagement with his poems? Is there another project in your head?

BFR: With his poetry, not right now. I’m still writing music for Yiddish poetry, and doing something with the poet Celia Dropkin who wrote really sexy poetry in Yiddish. It’s pretty racy—and so I’m setting some of those at the urging of a few Yiddishists who are really into that poetess. That’s one of the next projects.